30

April

2025

What were they thinking?

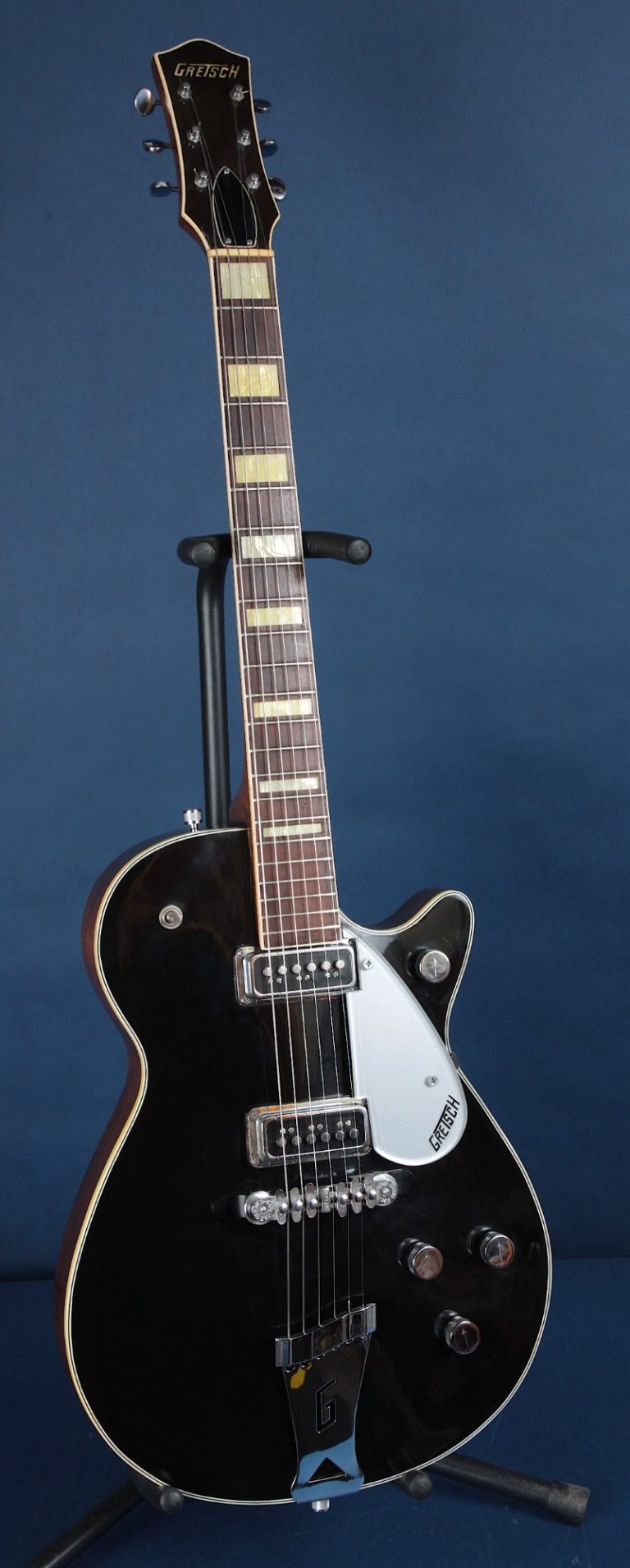

It is not uncommon to see guitars which have had work done by well meaning do-it-yourselfers, that, to be kind, wasn’t up to the task. Those repairs wander in every day and have to be carefully undone. It is a rarer thing to see original construction techniques in higher end instruments which render one speechless. Such was the case with the recent acquisition (no, I won’t be parting with it) of a 1956 Gretsch 6128 Duo Jet.

The guitar came into the shop, remarkably clean (save for some corroded chrome), but with two major issues.

The first was that the two pickup volume pots were frozen in place, heavily corroded. Thankfully, the dual stacked tone pot was working just fine. Two new 1 meg Reverse Audio Taper pots were secured and installed. Of course, at that point, the old wiring showed plenty of evidence that it was falling apart, so the pickups were sent down to Tom Brantley at Brantley Rewinds for new leads. Once returned, a new wiring harness was configured, everything went together smoothly and the growl of those Dyna Sonic pickups sang once more.

The second issue was that the guitar needed a neck reset. The neck heel was separating from the body and the action was unplayably high. Gretsch necks from the 1950s can be very tricky, as the methods used to assemble them varied widely and wildly. Some necks are held in with hidden screws. Some use a mortise and tenon joint while other use a more standard dovetail. So, disassembling this neck / body joint had to be done with the utmost care and caution.

There was plenty of wiggle in the neck joint, but it would not come free on its own. I could not find a screw holding the neck in place (Gretsch was known to hide them!) and the neck did not want to slide outward as a tenon would slide out of a mortise. It was clear that it was a dovetail joint, but something was holding it more tightly than it should have been.

Plenty of steam, plenty of gentle wiggling and more patience than anything else, and it finally came free. What a mess. This was the most bizarre neck joint I have ever seen.

Effectively, the neck block in the body held a standard dovetail receiver, but the neck itself had been made with a straight tenon. In assembling the guitar, the neck was slipped into the dovetail, leaving two triangular gaps on either side of the neck tenon. Then, triangular blocks of Mahogany were cut, shaped and added to fill in those gaps and create the dovetail. Next, everything was slipped back out and a hole was drilled laterally through the Mahogany blocks and neck tenon in order to glue in a spline to hold everything in place. Finally, two holes were drilled into the tenon along the narrowest points of the dovetail, and 1/8” dowels were inserted, vertically, which pin registered into the bottom of the neck block and the underside of the fretboard.

Broken pieces were carefully fished out of the neck block and reglued onto the dovetail, the dowels were reset, and new shims were fashioned to snug up the sides, before everything could be glued back together and the reset completed. But I could not help thinking that the assembly of this neck was unnecessarily complex.

Then, it occurred to me that I was making a mistake by thinking of this from the point of view of a repair tech. I needed to try to imagine the original guitar, on the bench, being assembled back in 1956. My best guess is that the guitar was assembled without the fretboard, so all of the fitting was done from the top down. The neck tenon would be laid in and centered, and then the mahogany blocks fitted on either side. Once done, the spline was set in place (a little proud on each side), and the dowels were added. The rounded bumps of the sides of the dowels and the protruding spline served as shims to tighten the overall joint before gluing. Then, the fretboard was glued on, pin registered on the tops of the dowels. From the point of view of the original builder, it was more a matter of fitting jig-saw puzzle pieces together than anything else. Still needlessly complex if you ask me, but if the guitar was built after a three martini lunch, it may have made a lot more sense at the time.

Now completed, I have a stunningly beautiful, 1956 6128 Duo Jet, a centerpiece of my personal collection. With a quick action and some of the finest rock and roll pickups ever attached to the top of a guitar, the Duo Jet was George Harrison’s first high quality axe (he played a 1957) and featured on many of the Beatles’ early recordings. You can see his original 1957 on the cover of the “Cloud 9” album. Other famous practitioners were Cliff Gallup and Bo Diddley. These guitars are hard to find, harder still in this condition. But, the DeArmond made Dyna Sonic pickups were used on many guitars of that era and should become a routine part of your vintage searches. Watch for them on early 1960s Guild T-50s and Starfires, and the Regal R270, made by Harmony. If you are playing roots rock, jazz, surf or country, you need a set of Dyna Sonics.

Keep on twangin’!

2

Apr

2025

A Rose By Any Other Name...

We live in an era of branding. These days, how an item will be branded, how it will be marketed, is actually worked out before the item is even manufactured. This extends to everything we consume in our lives, from the tangible products we use every day, to our movies, music and even our novels. In the world of guitars, we chase down our favored brands: Gibson, Martin, Fender, Gretsch, Rickenbacker, Guild, and swear our fidelity to those makers even before the new models hit the floor (some with a thud).

The trend has been toward a consolidation of major brands, through corporate buyouts and mergers. Coupled with our web based ability to acquire anything we want at the click of a mouse, Anything is Everywhere and, over time, the major brands brush aside everything else through sheer force of advertising and branding capital.

It wasn’t always so. During the early part of the twentieth century, right up through the Second World War, your choices for purchasing a musical instrument were essentially four; you could purchase it through a mom and pop local retailer, through a regional department store, from a door to door traveling instrument salesman (yep, they existed - my wife has a 1932 National Steel that was purchased in just this manner for her grandmother), or through a catalog retailer.

One common thread among the sellers of instruments is that they wanted to discourage comparison shopping, by selling products unique to their store, to their brand. And so begat the rise in House Brands, particularly among regional department stores and the catalog retailers. To fill this niche, companies like Harmony, Kay, National and yes, even Gibson, manufactured guitars under a wide variety of brand names.

Chief among these was the Harmony company, which was the single largest instrument manufacturer in the world. During the period of the Great Depression, Harmony manufactured guitars under more than seventy separate brand names. Many of these guitars are instantly recognizable as they are just different names atop standard Harmony models. Others feature unusual design motifs and artwork, designed to set them apart from anything else on the market, only available at your local department store. To be sure, there are many “ugly duckling,” low end instruments among them.

But there are quite a few swans, if you know where to look.

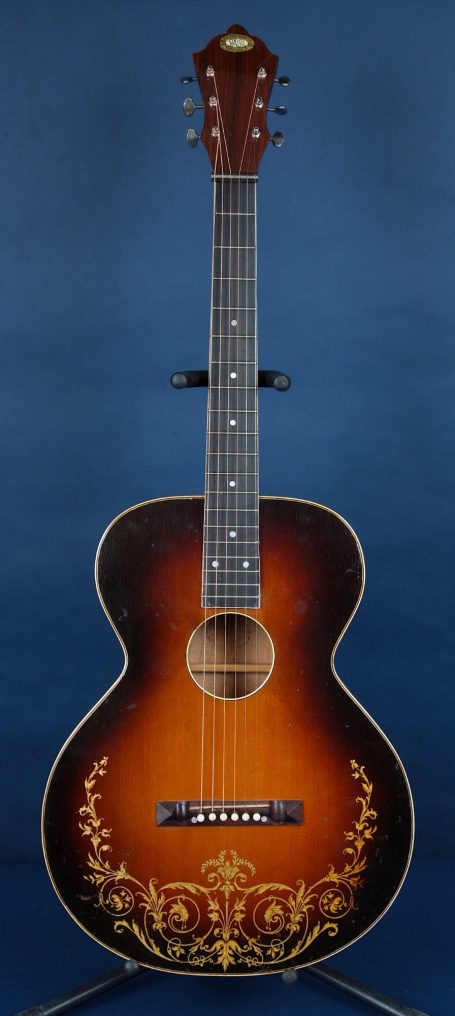

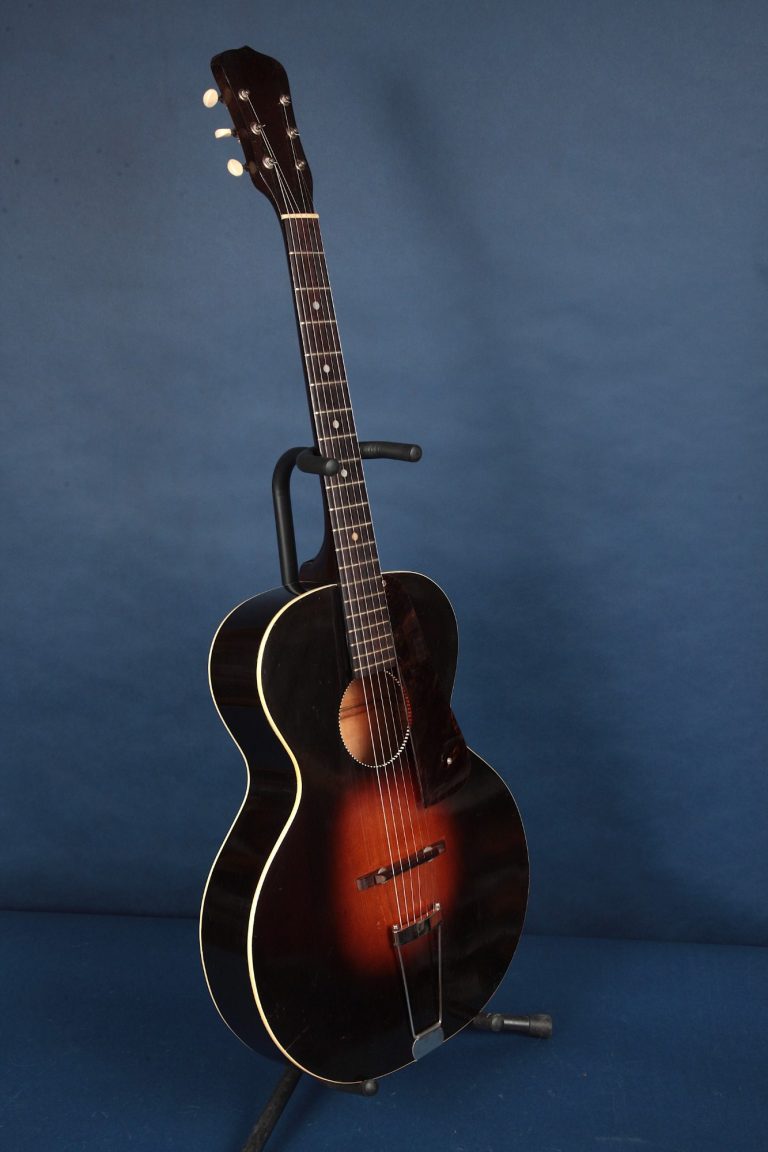

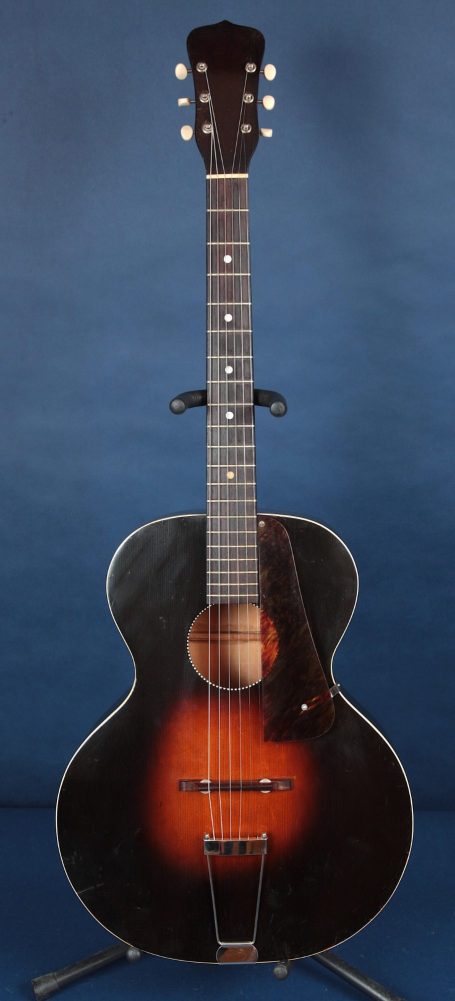

One such instrument popped into the shop early this month, a 1936 Supertone 255 archtop, sold through Sears Roebuck and made by Harmony, following the essential design of their Cremona line of archtop guitars. This was the top-of-the-line Supertone, and is exceptionally rare. Searching the internet, we managed to find only one other photographed example.

Like all of the Harmony acoustic guitars, it used solid tone woods throughout, with a Spruce top, Mahogany Back, Sides and Neck, Brazilian Rosewood Fretboard, Mother-of-Pearl inlays on the fretboard and real wooden bindings on the top. With a 15 1/2” lower bout and a deep V profile neck, this is a tight, punchy archtop with great sustain and tonal balance.

Coming into the shop, it needed a good bit of work, including a neck reset, two replacement inlays on the fretboard, the gluing of some open seams along the back, a lot of fretwork and the fitting of a new bridge. The guitar also bore the scars of a lifetime of playing, minor scratches and nicks that served to take a good bit of the blush off the rose. After completing the structural repairs and reset, it was time to tackle the finish. Generally speaking, I am opposed to refinishing vintage guitars, so nothing was done to sand or otherwise remove the original finish. Instead, by carefully matching the original stains, it was possible to fill in the majority of the nicks and dings, before polishing the guitar to a uniform shine. The results have been remarkable. The guitar plays with a comfortable action and looks much like it did when it was first sold some 89 years ago.

It is always a thrill to bring back to great playing condition, a fine guitar from yesteryear. It is still more of a joy to bring it back to a condition where a new player can fall in love it it for the first time. If you are as drawn to vintage guitars as I am, be sure to study up on the catalog and department store guitars from the Depression. There are plenty of diamonds in the rough lurking out there.

12

Feb

2025

Guitarcheology

These days, everything in our world exists as a “Brand,” a quantifiable product or service, a known commodity. Marketing is the essence of successful market share, and thus it is natural that those things we purchase or consume exist for us in a world of their own mythology, complete with fan clubs, spokespeople and pedigrees. Say the magic words: Gibson, Fender, Martin, Guild, Gretsch, Rickenbacker, and guitarists everywhere can picture their favorite models, the artists who play them, and on what great recordings they appear.

It wasn’t always so.

In 1930’s America, during the Great Depression, the makers of our cherished musical instruments teetered on the verge of their own economic collapse. At that time, there were no Big Box musical instrument retailers. Instead, instruments were typically sold in one of three ways: through stand alone Mom and Pop music shops, in regional or national department store chains, or through the famed catalog retailers like Sears, Spiegel and Montgomery Ward. Of them, the Mom and Pop shops were the most important, because the relationships formed between the customer and the shop were such that they were the best source of repeat business.

So, it was vital to protect those stores and keep them viable. Gibson, which sold most of its instruments through those small retail shops, was contractually obliged to them to not undercut the Mom and Pops by wholesaling their guitars at lower rates to the department stores and catalog giants. This left Gibson between a rock and a hard place. At a time when most consumers had little to no disposable income, it was essential to find a way to get more affordable instruments to market, get what could be gotten out of their sale, and keep the lights on at the factory.

Gibson, Harmony and Kay guitars, probably the three biggest manufacturers by volume, kept those lights on by manufacturing instruments under a slew of different names, and distributed them through all of the various outlets. We know of quite a few of them: Kalamazoo, Recording King, Cromwell, Kel Kroydon, Silvertone, Airline, Alden, Oahu. Gibson alone manufactured instruments under a little over thirty different brand names, and Harmony somewhere between fifty and sixty. Many of these instruments found their homes in the catalog companies, where those unusual brand names allowed for them to be sold as “House instruments,” guitars you could get through that store and no where else.

To make this all work, it was often the case that the off-brand instruments had to be simplified in construction, ornamentation and design, so they could be made more efficiently and therefore be less costly to produce to the manufacturing company. They also had to look different enough that a knowledgeable consumer would not readily see that this was a Gibson masquerading as something else. As an example, in Gibson acoustic guitars manufactured for the catalog and department store markets, X-Bracing gave way to ladder bracing, fancy inlays were simplified, the patented Gibson Truss Rod system was sidelined, and headstocks took on new shapes. Body shapes generally stayed the same, finishing techniques stayed the same, tone woods were less figured. In the end, a guitar is a guitar; these just looked and sounded a little different.

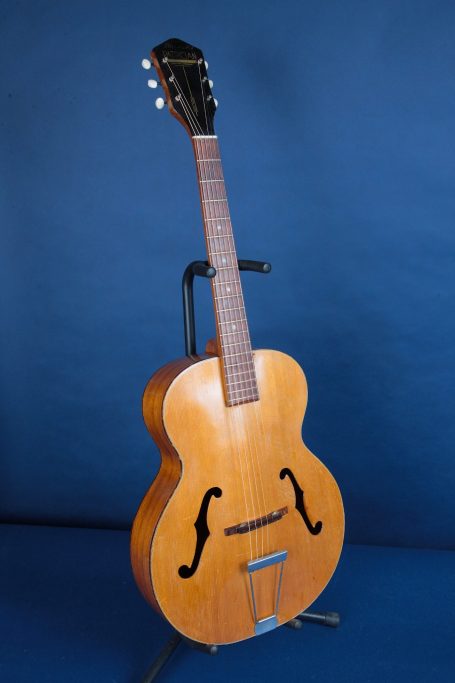

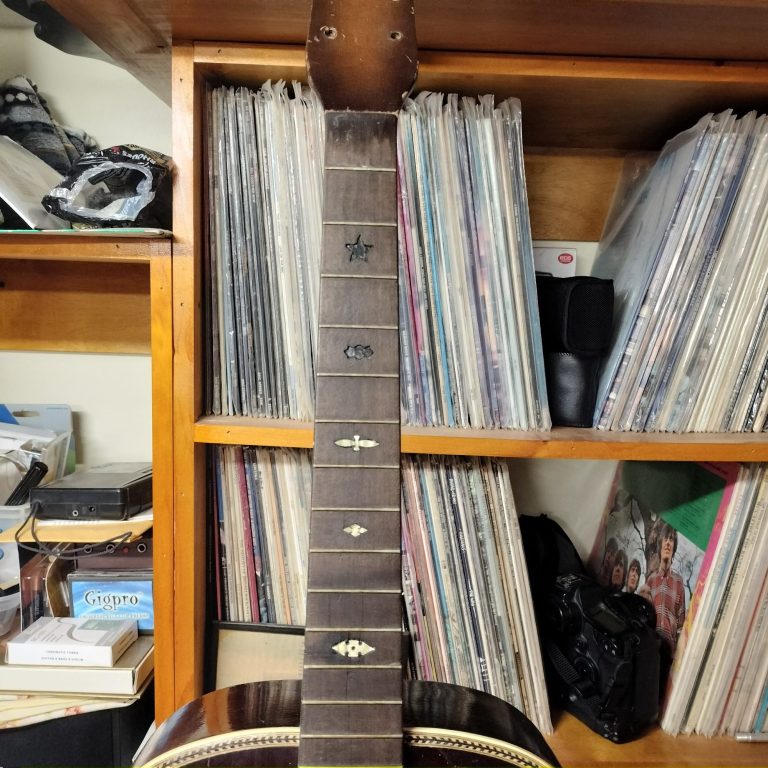

This past month, we took in a strikingly beautiful acoustic flat top with an arched back, floating bridge and trapeze tailpiece. It had no serial number, no FON number, and no brand name on the headstock. But, in design and appointments, it was clearly a guitar from the 1930s. The question became, “Whose guitar was it?”

We wound up looking at four distinct features of the guitar to try to make a determination on its provenance: the width of the lower bout, the unusual checkerboard design of the sound hole trim, the neck profile and the shape of the headstock. After many hours of painstaking research, we did not turn up a single example of a guitar that was entirely like this one. There was a Kay guitar that looked something like this from a distance, but all of the four parameters were different.

Still, what we had on the bench held enough clues to sort it out. The lower bout, at 15 5/8” wide, is the same size as a 1930’s Gibson dreadnought (and of a Martin, to be precise), while the aforementioned Kay had a lower bout of 15 7/8”. The neck profile is a classic V profile, common to Gibson guitars, and the binding at the sound hole, often referred to as a “zipper” binding, was found, as far as we can tell, on Gibson guitars, for only one year, 1932.

That left the headstock. while a number of manufacturers used paddle style headstocks somewhat similar to this, the only ones we could find that were exact matches for the one on our guitar, with rounded corners and a chamfered front to back edge, were on some of the Kalamazoo models, a number of the Recording Kings, and on the lesser known Cromwell and Capital guitars. All were made by Gibson.

What we have, we are fairly certain, is a Gibson made Acoustic Flat Top from 1932 (or 1933 with leftover parts!). It is ladder braced (we had to reglue two of the braces) has a 26” scale, and plays like a dream. It has a voice that is among the loudest I have ever heard on an acoustic guitar, with a crisp snap of an attack and a resonance that borders on having its own echo.

In the end, the lack of a specific brand name on the headstock probably indicates that this was a guitar made and sold as a “stencil,” an instrument wholesaled without brand markings, so a retailer could affix, inlay or engrave their own, creating a proprietary “House Brand” in the process.

The lesson? If you come across an old guitar that feels solidly built and sounds great, do not dismiss it for lack of a well known brand name. Many of these older instruments were made by folks who really knew what they were about, and unique voices from a bygone era could be yours for a song.

31

JAN

2025

Line and Form

Like a graceful sailing ship, the magic of a guitar or mandolin is all about line and form. When I work to bring an instrument into its best playing shape, it is about observing those lines and subtle curves, and how they relate to action, to transmission of string vibrations, to the production of the best tone that instrument can produce.

Among the instruments in the shop this month were two that needed neck resets, action adjustments, tonal optimization and minor repairs. These are indicative of the kind of daily work I am pleased to do.

The first was a lovely Bacon Mandolin from the 1920s, in good overall shape, but the victim of prior repairs that were a little hit or miss. The action was unplayable, the tone poorly defined, there was some old water damage to the tail of the instrument which had caused the wood to warp and separate, and a chip that had been taken out of what was effectively, the heel cap. The neck was loose in the joint and the bridge had been lowered to counter the set of the neck, resulting in a lower break angle without being able to lower the action.

First things first, the bridge had to be reshaped to fit the contour of the top of the mandolin. This is an absolute requirement for proper transmission of vibration from each string to the top and thus to the body of the instrument. Once corrected, the bridge was set at a better height to provide a higher break angle and the neck’s degree of underset was established relative to that new height.

From there, some simple geometric calculations determined just how much material had to be removed from the neck heel to correct the angle; a little adjustment goes a very long way. The neck was removed and was found to be based not on a dovetail, but on a dowel joint, one that had never been fully glued into place! After removing a tapered wedge of material from the heel of the neck, and shaving the dowel to allow it to reseat in its pocket at the correct angle, a new fretboard extension shim was added to keep everything straight and the neck was reglued.

The separation at the tailblock was a major concern. When an instrument gets soaked with moisture, the resulting damage can be to both the wood and the hide glues which hold pieces of wood together. The damage to the wood of this old Bacon was not the kind that could be returned to its original state; the best option was to fill the joint first with glue to hold pieces together, and then with a stainable filler to make for a more pleasant (if somewhat scarred) appearance. Similarly, the chip which had come out of the heel cap, had to be filled with a tiny piece of delicately shaped Maple, which could be glued to the damaged area and blended in.

After a fret leveling and crowning, stringing and set-up, the result is a great playing mandolin, with a silky smooth action and a high break angle, insuring great transmission of string vibration to the instrument, and a pure, well balanced voice.

The second instrument is a mid-1960s Harmony H165, the “Poor Man’s Martin,” a solid Mahogany OM sized acoustic most closely akin to a Martin 00-17. These ladder braced guitars have great voices, depth and warmth, and are possibly the best value in vintage guitars on today’s market. Top and Back are both one piece, something that you just don’t see in a contemporary guitar. However, in typical Harmony fashion, the guitar was never shimmed properly. Instead, it was slogged together with ample amounts of hide glue to fill the dovetail cavity and hold things in place. Time had taken its toll. The neck joint was pulling upward at the heel, the action was high enough to get a Mazda Miata under it, and a prior owner had lowered the saddle to just above the height of the bridge slot, effectively killing the tone of the guitar with a nearly flat break angle. The degree of neck underset was noted and a measurement was calculated to bring that line of the fretboard back to about a millimeter above the bridge. The neck was removed, the angle adjusted, the joint properly shimmed and everything put back together. Now, the guitar sports a nice high saddle in conjunction with a fast action (5/64ths Low E, 1/16 High E at twelfth fret) and, strung with Silk and Steel strings, sings with a warm, bluesy tone that has both depth and presence. I love these guitars and actively seek them out; they never disappoint.

Line and form. The line of the fretboard and of the string, the geometry of the triangle they produce, the vibration arc of the string in motion, the shape and height of the saddle, the tension on the string introduced by the break angle, the fitting of a floating bridge to the curved top of a mandolin. Bringing these elements together is like bringing the stars into alignment (though nowhere near as difficult), and the result is the best sound and playability that instrument can produce.

The creative spark of the artist? Well, that is up to you.

Bacon Action After Reset

After a reset and the proper shimming of the fretboard extension, the action is smooth as silk.

Bacon Bridge Fit

The Bridge must make a clean contact with the top for optimal vibration transmission.

Chip Repair

Fitting this tiny piece took almost as much time as the reset!

Part Two

Harmony H165 - "The Poor Man's Martin"

Photos of the restored H165, including the dovetail joint, ready for reshaping to the new angle, the new bone saddle, optimized for a better break angle and great tone, and the low, 5/64ths action at the twelfth fret. This guitar is an absolute joy to play.

30

DEC

2024

Gotta relieve that tension

Too much tension is not good for our health. Nor is it good for the health of a guitar. I work on a lot of instruments from the 1920s through the 1970s, and I see a lot of guitars that have been stored for years, under tension. That can wreak havoc on a neck, a bridge, or a top, and many guitars need attention in one or more of these areas to return them to playability.

This December, I worked on four instruments suffering from too much tension. The first was an Oahu 71K Jumbo Lap Steel (square neck), made by Kay in the 1930s. Over the years, the tension had caused the bridge to crack behind the bass side of the saddle, and for the bridge to begin to separate from the top. Fortunately, as a lap steel, the action was meant to be high, so there were no neck issues of note. The bridge crack was repaired and the bridge reattached, and the guitar is now listed in our shop.

Next, I had to tackle a Harmony Sovereign H1260, their Jumbo dreadnought, and this one needed much more attention. Once again, the stress of being left under tension, had impacted this guitar, causing the neck to dip and rendering the action unplayable. There were a couple cracks in hard to reach places along the endpin which had to be cleated and glued from inside, a nut that had to be reset, and a new heel cap to fabricate, but more importantly, the neck heel was cracked in half and the neck angle necessitated a full-off reset. Fortunately, the hide glues with which almost all good guitars are constructed, allow for everything to be taken apart again for repair. The neck heel was carefully drilled, dowelled and glued, the angle of the neck corrected to bring down the action (and raise the saddle for a better break angle at the same time), and the frets were crowned and leveled. The result is an absolute tone monster of a guitar. These old H1260s have a wonderfully complex tone, big and round in the bottom end, and warm and bright, without being shrill, up top. It is no wonder that they have long been studio favorites (see: Jimmy Page and "Stairway to Heaven").

Next up was a lovely Giannini Craviola CRA-12S, a 12-string acoustic. The action was a bit high (even for a 12-string) and initially, I had hopes of taking the neck off to give it a full reset. However, this guitar was assembled (or possibly, reassembled at some point) with a non-reversible epoxy and that neck just would not budge (Ovations and Harptones are infamous for this). So, the culprit had to be found elsewhere, and it turned out to be a belly behind the bridge (again, the result of excessive string tension). A JLD Bridge Doctor was the prescription, coupled with light gauge strings tuned a whole step down, and the sweet jangle of that Giannini was returned, this time with a wonderfully playable neck.

Lastly, I worked on an older Harmony Patrician 1407 archtop, which had needed a neck reset for a long time, and which a prior owner had attempted to deal with by cutting the bridge slots lower and lower. Ultimately, all he did was to flatten the break angle to the point where the tone was strangled right out of the guitar. When all else fails, you've gotta do what you should have done the first time. The neck came off, the angle was corrected, the bridge slots were filled and set to the proper radius of the fretboard, and a sweet little archtop was brought back from the brink. It isn't an L-4, but put a DeArmond Rhythm Chief on it and it will be a killer blues or roots machine.

The new year is on us. Resolve to treat yourselves a little better, find ways to relieve that tension in your own life and, when not in regular use, on your stringed friends. They'll thank you for it!

Geoff